Research Article - (2023) Volume 9, Issue 1

Received: 26-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. IPCP-23-15572; Editor assigned: 30-Jan-2023, Pre QC No. IPCP-23-15572 (PQ); Reviewed: 13-Feb-2023, QC No. IPCP-23-15572; Revised: 20-Feb-2023, Manuscript No. IPCP-23-15572 (Q); Published: 27-Feb-2023, DOI: 10.35841/2471-9854.23.9.007

Background: People with obesity often suffer from distress and psychopathological symptoms that diminish after undergoing bariatric metabolic surgery; however, the confinement caused by the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the general population in this sense. Considering that the bariatric population has a higher risk for the development of these disorders, it is important that they are identified in order to prevent or treat them opportunely thus avoiding health risks. Therefore, this study aims to determinate the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic related distress and psychopathological symptoms in persons after bariatric metabolic surgery.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted including 102 participants with more than six months of undergoing bariatric metabolic surgery. Sociodemographic information was collected, as well as the COVID-19 related psychological distress and the psychopathological symptoms measured by the SCL-90R. A path analysis was used to evaluate the correlation between the variables.

Results: 90.2% of the participants were women, 84% had been under surgery with a Sleeve Gastrectomy technique while the rest underwent Roux-Y Gastric Bypass. The obtained model showed a significant correlation between the SCL 90-R subscales and the COVID-19 related psychological distress and both were negatively correlated to participants’ age. The model had adequate goodness-of-fit indicators (Chi-square goodness-of-fit (χ2): 78.007, df: 64, p: 0.112; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA): 0.047; Goodness of Fit Index (GFI): 0.907; Comparative Fit Index (CFI): 0.991; Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PNFI): 0.670; Akaike Information Criterion (AIC): 160.007).

Conclusion: The psychological distress caused by the pandemic and confinement is evidenced by higher scores on the SCL-90R instrument. However, further studies and psychometric tests with more homogeneous samples with respect to sex and surgical technique are needed.

Bariatric metabolic surgery; Correlation of data; COVID-19; Gastrectomy; Psychological distress

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was reported for the first time in the city of Wuhan (China) in December 2019 [1]. Particularly in Mexico, the first confirmed case was reported on February 27, 2020, reaching 10,000 cases by April 17 of that same year, within the most affected areas was the city of Tijuana, Baja California, a municipality in the northwest of this country, which has the third largest number of inhabitants (more than 1.7 million) and shares the world’s busiest border with California (United States). Therefore, Tijuana may have been subject to earlier exposure to COVID-19 than the rest of Mexico due to the import of cases from California. By May 11, Tijuana had the highest number of deaths from COVID-19 of any municipality in Mexico (170 deaths), and the highest mortality rate (17.3 per 100,000 people) almost 6 times higher than the national rate of 3.1 per 100,000 people [2].

The mortality rate in this municipality can be attributed to another risk factor, which is that the northern part of the country has the highest prevalence of obesity, since more than 40% of the adult population suffers from this disease and it has been documented that a higher body mass index is associated with the risk of death from COVID-19 [3-7]. However, it is worth mentioning that not only people with obesity are vulnerable, also those who underwent Bariatric Metabolic Surgery (BMS) to lose weight due to micronutrient deficiency caused by the surgical technique itself and lack of adherence to the prescribed multivitamin supplementation, which has been reported worldwide with a prevalence of more than 70% representing a major threat to the health of the individual especially as micronutrients are essential in modulating the immune response [8-14].

The mortality figures and the risk factors listed above, together with the lifestyle change (social isolation and confinement) caused by the COVID-19 pandemic [15], have had a psychological impact on 53.8% of the apparently healthy population, the most prevalent symptoms being anxiety (28.8%), depression (16.5%) and stress (8.1%), other reactions that have been observed are uncontrolled fear related to becoming infected, feelings of loneliness, frustration and boredom, all of which have been shown to decrease psychological well-being and quality of life as they have been related to higher scores of psychopathological symptoms such as somatization (SOM), obsession-compulsion (O-C), interpersonal sensitivity (IS), depression (DEP), anxiety (ANX), hostility (HOST), phobic anxiety (PANX) and psychoticism (PSY) [16].

This study is of great relevance given the vulnerability of this population, since these persons tend to present this type of symptomatology especially anxiety and depression which could end up jeopardizing the success of the surgery, even their health and integrity as a person during the COVID-19 pandemic, since in addition to presenting “emotional intake” derived from poor self-control and a limitation in coping with stressful situations, with eating behavior being a mediator between these conditions [17,18] suicidal ideation associated with depression has been documented in persons after bariatric metabolic surgery [19,20].

Aim

The present study aims to identify the possible psychological distress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and its relationship with the development or increase of psychopathological symptoms, as well as self-perceived risk of infection by the virus in adults after bariatric metabolic surgery in adults from the northwestern border of Mexico.

Study Design and Participants

The present project is a cross-sectional study conducted in the City of Tijuana municipality of the state of Baja California, México between September and November 2021. The inclusion criteria were men and women, adults (>18 years old), of Mexican nationality, residents of the City of Tijuana who had been operated with the bariatric techniques of Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG) or Roux-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) at least 6 months before the start of the study. The sample size was non-probabilistic, a database of N=250 persons was consulted and those who met the inclusion criteria were contacted by telephone by the treating surgeon that was not part of the research team to be invited. A total of n=102 persons signed the informed consent (IC) format and were included in the study.

The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Autonomous University of Baja California, Mexico (1135/20- 2) on January 16, 2021. To comply with the World Health Organization (WHO) derived from the COVID-19 pandemic and to keep a safe distance all the formats used were adapted to be answered online through the Google Forms platform, the instrument was applied to measure the variables of interest, all this was done in a single 30 minutes session [21].

Data Collection

Sociodemographic information was collected using the personal identification card, which included seven items to evaluate the COVID-19 related psychological distress.

Data Items

Items

• Have you gotten sick with COVID-19?

• If you haven’t gotten sick, are you afraid of getting sick?

• Do you think you’re at increased risk for COVID-19 due to bariatric metabolic surgery?

• Have any close family members become ill with COVID-19?

• Have any close family members died from COVID-19? had dichotomous answers (yes or no); The degree of confinement was measured with item

• How many days a week do you stay at home?, answer options were: More than five days, between three and five, less than three, none.

• Finally, do you know what the risk factors are for contracting COVID-19? Was an open answer question regarding the person’s knowledge about the risk factors for contracting COVID-19 due to the BMS?

The participants answer was evaluated by an infectology expert depending on the degree of agreement between the information given by the participant and the reference information published by the WHO. The answers were categorized to “zero” when the information that the participant gave did not coincide with the reference information and “one,” when the information coincided with the reference information.

Symptom Checklist 90-R

To measure the participants psychological distress, the modified Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL 90-R) by Derogatis was used [22]. The SCL90-R is a self-report questionnaire, assessing general psychopathology and clusters of psychiatric symptoms, which was suggested by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Metabolic Surgery as a valid screening measure to be used in the psychosocial evaluation and demonstrated good internal consistency and validity among candidates for BMS, the coefficients of the 9 scales between were 0.76-0.90 [23,24].

The questionnaire consists of 90 items with Likert-type responses ranging from 0 to 4 (0=not at all; 1=a little; 2=moderately; 3=quite a bit; 4=extremely). The participant responded to each item according to their discomfort during the week before the application of the questionnaire. The scores for each factor were obtained by looking for the scores’ average (sum of items divided by the number of items).

The test is divided into nine subscales, Somatization (SOM): Discomfort related to different bodily dysfunctions (cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal) and physical pain (headache, low back pain, myalgia); Obsessive-Compulsive (OC): Thoughts, actions and impulses that are experienced as inevitable or unwanted; Interpersonal Sensitivity (IS): Feelings of inferiority and inadequacy, especially when the person compares himself to others; Depression (DEP): Dysphoric moods, lack of motivation, low energy, hopelessness and suicidal ideation; Anxiety (ANX): Symptoms of nervousness, tension, panic attacks and fears; Hostility (HOS): Characteristic thoughts, feelings and actions of the presence of negative affections of anger; Phobic Anxiety (PANX): Persistent fear responses that are irrational and disproportionate to the stimuli that provoke them (specific people, places, objects, situations); Paranoid Ideation (PI): Paranoid behaviors, thoughts of suspicion and fear of loss of autonomy; Psychoticism (PSY): States of loneliness, schizoid lifestyle, hallucinations and thought control; and additional items referring to Clinical Symptoms (CS): Loss of appetite, trouble sleeping, thinking about dying or dying, overeating, feeling guilty. The instrument also includes the three global scales, the Global Severity Index (GSI), Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI), and the Positive Symptom Total (PST).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were obtained from the sociodemographic data, the 10 sub-scales of the instrument and the 3 global scales. Cronbach’s alphas were calculated for each of the 10 predefined factors of the SCL-90-R to determine the internal consistency of the instrument. Spearman and Pearson correlations were also carried out between the SCL-90-R instrument subscales, the sociodemographic variables and the COVID-19 related psychological distress items. SPSS version 25 software for Windows was used for data processing and analysis. A p-value is smaller than 0.05 indicates the presence of statistical significance.

Structural Equations Model

A hypothetic model was created using the SCL90-R and the COVID-19 related psychological distress items as endogenous variables and the internal perceived psychological distress (Factor 1) as well as COVID-19 related psychological distress (Factor 2) as exogenous variables.

A maximum-likelihood solution for the hypothetic model was obtained using an Analysis of Moment Structure Program [25]. The latent factors internal perceived psychological distress and COVID-19 related psychological distress were used to estimate the sample variance-covariance matrix. The model fit was measured by the chi-square goodness-of-fit test as well as the generally accepted measures of global fit Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA); the Comparative Fit Index (CFI); Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PNFI) and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [26].

Acceptable fit values for chi-square goodness of fit test, CFI and PNFI are close to 1.0 with acceptable RMSEA cutoff values being close to 0.06 and lower values of AIC indicate a better fit [26-28]. In the results section, the final adjusted solution is presented.

Sample Characteristics

The sociodemographic data indicated that 90.2% of the participants were women with a mean age of M=39.77, SD=1.05, and 9.8% men with a mean age of M=39.8, SD=9.7; 84% had been under surgery with a SG technique while the rest underwent RYGB. Regarding the elapsed post-surgery time, 50% had been under surgery between one and three years ago, followed by 27.5% between 6 months and 1 year, and 22.5%, more than 3 years, the rest of the sociodemographic data can be seen in Table 1.

| Variable | % | n |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 9.80% | (n=10) |

| Female | 92% | (n=92) |

| Sample size | n=102 | |

| Surgical Technique | ||

| Sleeve gastrectomy | 84% | (n=85) |

| Roux-Y Gastric Bypass | 16% | (n=17) |

| Time since surgery | ||

| 6 months to 1 year | 27.50% | (n=28) |

| 1 to 3 years | 50% | (n=51) |

| Over 3 years | 22.50% | (n=23) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 33.30% | (n=34) |

| Married | 48% | (n=49) |

| Divorced | 7.80% | (n=8) |

| Consensual union | 8.80% | (n=9) |

| Widower | 2% | (n=2) |

| Education | ||

| Elementary school | 5.90% | (n=6) |

| Middle school | 12.70% | (n=13) |

| High school | 23.50% | (n=24) |

| University | 49% | (n=50) |

| Master | 8.80% | (n=9) |

| Occupation | ||

| Unemployed | 2.90% | (n=3) |

| Housewife | 2.60% | (n=21) |

| Employee | 50% | (n=51) |

| Businessman | 22.50% | (n=23) |

| Student | 2.90% | (n=3) |

| Retired | 1% | (n=1) |

| Employment situation during the pandemic | ||

| Working from home | 52% | (n=53) |

| Leaving home to work | 34.30% | (n=35) |

| Unemployed since before the pandemic | 4.90% | (n=5) |

| Unemployed due to the pandemic | 8.80% | (n=9) |

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample included in the study.

SCL 90-R Internal Consistency

The SCL 90-R Scale has previously been used in Mexican population however it has not been reported on Mexican persons after BMS, therefore Cronbach’s α score were obtained and compared to the ones reported by Derogatis, 1994, and Cruz Fuentes et al., 2005 to determinate the internal consistency of the instrument in this sample [29] (Table 2). The full scale presented a good reliability according to its Cronbach’s alpha scores since with the exception of CS all subscales showed α score above 0.85.

| Internal Consistency (Coefficient α) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 2b | 3c | |

| Somatization (SOM) | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.86 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive (OC) | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.87 |

| Interpersonal Sensitive (IS) | 0.86 | 0.76 | 0.91 |

| Depression (DEP) | 0.9 | 0.83 | 0.91 |

| Anxiety (ANX) | 0.85 | 0.8 | 0.88 |

| Hostility (HOS) | 0.84 | 0.66 | 0.89 |

| Phobic Anxiety (PANX) | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.85 |

| Paranoid Ideation (PI) | 0.8 | 0.69 | 0.86 |

| Psychoticism (PSY) | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.87 |

| Clinical Symptoms (CS) | - | - | 0.76 |

Table 2: SCL 90-R Scale alpha scores of three populations.

SCL 90-R Scores

The means and standard deviation (raw scores) from the subscales of the SCL 90-R in the current sample are shown in Table 3. It can be noted that the subscales of OC (0.71 ± 0.62) and DEP (0.69 ± 0.65) as well as AI (0.69 ± 0.57) showed the highest means while PSY (0.28 ± 0.48) was the lowest.

| Subscale | Mean | S.D |

|---|---|---|

| Somatization (SOM) | 0.65 | 0.49 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive (OC) | 0.71 | 0.62 |

| Interpersonal Sensitive (IS) | 0.52 | 0.68 |

| Depression (DEP) | 0.69 | 0.65 |

| Anxiety (ANX) | 0.47 | 0.55 |

| Hostility (HOS) | 0.53 | 0.65 |

| Phobic Anxiety (PANX) | 0.31 | 0.54 |

| Paranoid Ideation (PI) | 0.55 | 0.69 |

| Psychoticism (PSY) | 0.28 | 0.48 |

| Clinical Symptoms (CS) | 0.69 | 0.57 |

| Global Severity Index (GSI) | 0.55 | 0.52 |

| Positive Symptom Distress (PSD) | 1.35 | 0.4 |

| Positive Symptom Total (PST) | 33.23 | 2.91 |

Table 3: Means and S.D for current sample.

Psychopathological Dimensions and COVID-19 Related Psychological Distress

Table 4 provides the correlation coefficients for the associations of the sociodemographic variables, COVID-19 related psychological distress items and the SCL 90-R subscales and global indices. A significant association was found between the age of the participants and OC, IS, DEP, HOS, PANX and PI as well as the GSI and PST. The only COVID-19 related items that showed a significant correlation with the SCL 90-R subscales were the Fear of contagion, Awareness of the risk of contagion due to BMS and Knowledge about COVID-19 risk, nonetheless they showed a significant correlation with all of the subscales as well as the general indices.

| Sociodemographic variable | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 Related items | Sex | Age | Marital status | Education | Employment situation during the pandemic | Occupation | |||||||||

| Have you gotten sick with COVID-19? | -0.028 | -0.074 | -0.19 | 0.006 | .453** | 0.101 | |||||||||

| If you haven't gotten sick, are you afraid of getting sick? | 0.069 | 0.052 | -0.013 | 0.078 | -0.003 | 0.005 | |||||||||

| How many days a week do you stay at home? | -0.139 | 0.158 | .355** | -0.09 | -0.071 | 0.041 | |||||||||

| Do you think you're at increased risk for COVID-19 due to bariatric metabolic surgery? | -.209* | -0.011 | 0.06 | -0.01 | -0.124 | 0.09 | |||||||||

| Do you know what the risk factors are for contracting COVID-19? | -.217* | -0.026 | 0.059 | -0.01 | -0.123 | 0.094 | |||||||||

| Have any close family members become ill with COVID-19? | -0.122 | -0.158 | 0.027 | 0.012 | -0.106 | 0.119 | |||||||||

| Have any close family members died from COVID-19? | 0.015 | -0.171 | 0.05 | -0.07 | 0.174 | -0.031 | |||||||||

| SCL 90-R Subscales and Global indices | |||||||||||||||

| Sociodemographic variables | SOM | OC | IS | DEP | ANX | HOS | PANX | PI | PSY | CS | GSI | PSD | PST | ||

| Sex | -0.072 | -0.09 | -0.064 | 0.038 | 0.034 | -0.082 | -0.093 | -0.043 | 0.017 | -0.125 | -0.062 | -0.122 | 0.17 | ||

| Age | -0.18 | -.261** | -.263** | -.279** | -0.154 | -.208* | -.257** | -.243* | -0.188 | -0.104 | -.250* | -0.185 | -.273** | ||

| Marital status | 0.104 | 0.086 | 0.083 | 0.053 | 0.099 | 0.156 | 0.009 | 0.089 | 0.05 | 0.052 | 0.084 | 0.09 | 0.085 | ||

| Education | -0.095 | -0.037 | -0.168 | -0.04 | -0.017 | -0.13 | -0.062 | -.243* | -0.079 | -0.064 | -0.085 | -0.128 | 0.055 | ||

| Employment situation during the pandemic | 0.067 | -0.035 | 0.134 | 0.011 | 0.113 | 0.168 | 0.105 | 0.097 | .253* | -0.035 | 0.072 | 0.08 | 0.032 | ||

| Occupation | -0.013 | -0.033 | -0.11 | -0.08 | -0.185 | -0.171 | -0.091 | -0.105 | -0.081 | -0.177 | -0.115 | -0.121 | -0.111 | ||

| SCL 90-R Subscales and Global indices | |||||||||||||||

| COVID-19 Related items | SOM | OC | IS | DEP | ANX | HOS | PANX | PI | PSY | CS | GSI | PSD | PST | ||

| Have you gotten sick with COVID-19? | 0.001 | -0.029 | 0.066 | -0.04 | -0.078 | -0.016 | 0.012 | 0.008 | 0.15 | -0.024 | -0.015 | -0.013 | -0.045 | ||

| If you haven't gotten sick, are you afraid of getting sick? | 0.182 | -0.134 | -0.145 | 0.051 | 0.112 | -0.147 | -0.112 | -0.146 | -0.022 | 0.111 | -0.026 | -0.033 | 0.102 | ||

| How many days a week do you stay at home? | .244* | .297** | .308** | .239* | .325** | .359** | .323** | .227* | .291** | .295** | .325** | .300** | .272** | ||

| Do you think you're at increased risk for COVID-19 due to bariatric metabolic surgery? | .228* | .399** | .446** | .386** | .234* | .363** | .305** | .292** | .333** | .376** | .422** | .379** | .400** | ||

| Do you know what the risk factors are for contracting COVID-19? | .221* | .398** | .452** | .413** | .261** | .375** | .355** | .356** | .359** | .379** | .427** | .387** | .406** | ||

| Have any close family members become ill with COVID-19? | 0.003 | -0.021 | -0.143 | 0.109 | -0.019 | -0.044 | -0.042 | -0.068 | -0.016 | 0.063 | 0.002 | 0.022 | -0.071 | ||

| Have any close family members died from COVID-19? | -0.007 | 0.101 | -0.004 | -0.01 | 0.131 | 0.065 | -0.028 | -0.052 | -0.011 | -0.053 | 0.007 | 0.055 | -0.144 | ||

Note: SOM = Somatization; OC = Obsessive-Compulsive; IS = Interpersonal Sensitivity; DEP = Depression; ANX = Anxiety; HOS = Hostility; PANX = Phobic Anxiety; PI = Paranoid Ideation; PSY = Psychoticism; CS=clinical Symptoms. *p< .05; **p< .01. Bold indicate statistical significance.

Table 4: Correlations of the sociodemographic variables, COVID-19 related psychological distress and SCL 90-R subscales.

Structural Equation Modeling

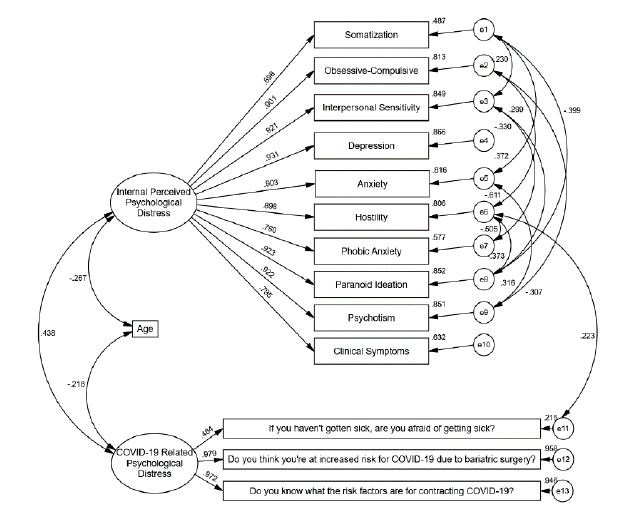

A structural equation model (SEM) was proposed and modeled using AMOS, the model included the variables that showed a significant correlation with the SCL 90-R subscales. In the graphical representation, rectangles are observed variables while circles correspond to residual errors, the values on the one sided arrows are standardized regression weights and double sided arrows indicate correlations.

On the first SEM, the internal perceived psychological distress (Factor 1) explained a high percentage of all SCL 90-R subscales, and was significantly correlated to the COVID-19 related psychological distress (Factor 2); also, both factors were negatively correlated to the participants’ age (Figure 1). Furthermore, Factor 2 only had a significant effect over the fear of contagion, awareness of the risk of contagion due to the BMS and knowledge about COVID-19 risk. Lastly the socio-demographic variables of sex, education, employment status during the pandemic and marital status showed no significant effect over the subscales and COVID-19 Related items that were previously correlated with. Considering these findings this SEM was modified to obtain a significant one with a better fit.

Figure 1: Hypothesized structural equations model of the symptom checklist 90-revised (SCL 90-R) and the COVID-19 related psychological distress items.

The rectangles represent the observed variables; the ovals represent the errors associated with the endogenous variables: e1-e10 correspond to the SCL 90-R subscales, e11-e17 correspond to the COVID-19 related psychological distress items. One way arrows are used to represent effects and two way arrows correlations. Goodness of fit indices: χ2=401.535, df=205, p=0.000; RMSEA: .097, GFI: .750, CFI: .879; PNFI: .696;AIC: 497.535.

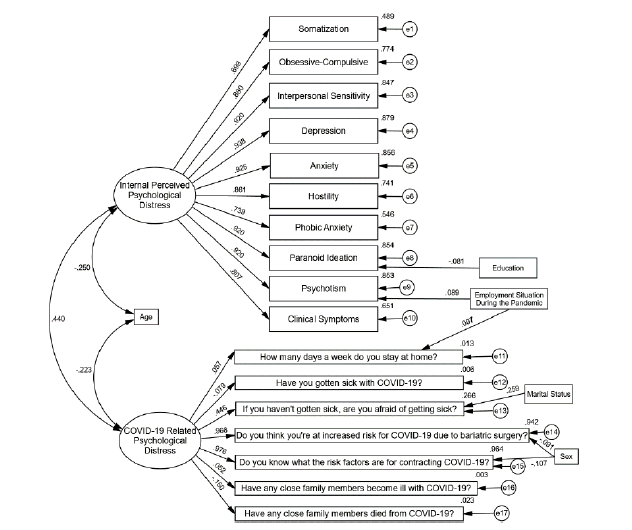

The final model shows the same effect of the psychopathological symptoms factor on all the sub-scales of the SCL 90-R instrument, with DEP being the one that was explained in the highest proportion, with 86.6% of variance explained, and SOM the lowest with 48.5% of variance explained. At the same time, similar to what was found in the inter-correlation tests; a correlation was observed between the residuals of subscales (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Final structural equations model of the symptom checklist 90-revised and the COVID-19 related psychological distress items

The rectangles represent the observed variables; the ovals represent the errors associated with the endogenous variables: e1-e10 correspond to the SCL 90-R subscales, e11-e13 correspond to the COVID-19 related psychological distress items. One way arrows are used to represent effects and two way arrows correlations. Goodness of fit indices: χ2=78.007, df=64, p=0.112; RMSEA: 0.047, GFI: 0.907, CFI: 0.991; PNFI: 0.670; AIC:160.007.

The psychological distress factor related to COVID-19 had a significant effect on the fear of contagion, risk perception and risk knowledge, with risk perception being the most explained with 95.8% of variance explained. As in the first model, a significant correlation was observed between both factors together with age. Also, the final model showed better goodness-of-fit indicators than the hypothetical model.

As shown in the internal consistency tests, the SCL 90-R instrument applied to Mexican individuals after BMS yielded higher Cronbach’s alpha scores than those reported by Cruz Fuentes et al., 2005, Derogatis, 1994, this may be due to a greater homogeneity of the characteristics of the sample, since in this study all the participants belonged to a cohort whose common characteristic were a history of morbid obesity and having undergone BMS [29,30].

Consistently with what has been found in Mexican individuals by Gonzalez-Santos et al., 2007 and Lara Munoz et al., 2005 and other types of target groups the instrument showed a high correlation between its subscales [31-33]. Such results clearly indicate that all of these dimensions are part of the same measurement instrument and that they can be incorporated into a general dimension, which in this case is represented by the global indices.

A significant correlation was observed in the proposed structural equation model between the psychopathological symptoms evaluated by the SCL 90-R subscales, the age of the participants and the psychological distress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The latter was explained only by three items, concerning the fear of COVID-19 contagion, the perceived risk of contagion due to BMS and the knowledge of the risk of COVID-19 contagion.

Those who were more conscious of the risk associated with a history of obesity and BMS, along with being aware of the risks associated with COVID-19 infection, expressed a greater level of fear of being infected by the virus, which in turn led to psychological discomfort, particularly in the form of hostility. This discomfort, as well as the other psychopathological symptoms evaluated, was negatively correlated with the age of the participants, as the youngest were the ones who showed higher scores in the instrument dimensions.

This study results indicate that the positive and significant correlation found between psychopathological symptoms and distress caused by COVID-19 proves that, although the SCL 90-R was not designed to evaluate the discomfort caused by a pandemic, the scores of the various dimensions increased due to the distress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Particularly factor 10 (CS) which refers to the presence of symptoms such as overeating, trouble falling asleep, awakening in the early morning and sleep that is restless or disturbed. Although this factor did not correlate with psychological distress by COVID-19, it is a cause for concern, as it scored high on average, which could contribute to the development of eating disorders that lead to weight regain and/or severe manifestations of depression and hostility, thus indicating the imperative need for the implementation of interventions aiming to improve the mental health of persons after BMS.

However, further studies and psychometric tests are required to clarify the effect of the pandemic and its confinement on BMS patients considering a more homogeneous distribution of sexes and surgical techniques, since the main limitation of this research was the high prevalence of females and people submitted to SG in the sample.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Psychology of the Autonomous University of Baja California (approval number: D245). All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in the 1964 World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Not applicable.

DLGS organized the project and designed the study. VHAS provided the participants database and collected the data. EAR analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All the authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript, and share the final responsibility for the decision to submit it for publication.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

We are grateful to my new life obesity center for the facilities granted during the research and in a particular way to each of the people who voluntarily participate in this project.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

Citation: González-Sánchez DL, Andrade-Soto VH, Armenta-Rojas E (2023) Psychological Distress during COVID-19 Confinement in Persons after Bariatric Metabolic Surgery. Clin Psychiatry. 9:007.

Copyright: © 2023 González-Sánchez DL, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.